My New Favorite Organism: The ogre-faced, net-casting spider

NOTE: This article, in a shorter form, originally appeared as a Halloween special-edition “Creature Feature” for The Ethogram. I expanded it for a fellowship application and decided to toss it up here as an instance of a series I might call “my new favorite organism”, highlighting the wonder of learning about an organism you’ve never even heard of before.

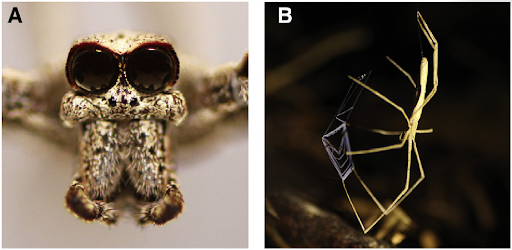

The ogre-faced, net-casting spider (Family Deinopidae: Deinopis spinosa) has a terrifying name and a “circadian Jekyll and Hyde” lifestyle to match [1]. During the day they appear as odd lumps in their home palm trees, but the night transforms them into fierce predators. These high-strung spiders literally take matters into their own hands, fashioning their silk into a net that they wield between their front legs. Hanging upside-down armed with this engineering and some patience, Deinopis spinosa should strike fear into any insect within range. Some are caught beneath the watchful Deinopid eye. Met with a forward strike of the web like sticky plastic wrap on a bowl of six-legged soup, walking insects stand no chance as they are bitten, wrapped, liquified, and consumed. The spider’s eyes are doing work here—Jay Stafstrom, who also dubbed them “some of the coolest spiders on the planet”, occluded their vision and found them no longer able to catch walking prey. But these blind spiders had no problem hunting flying prey [2]. What?!

A: The unique eyes of *Deinopis spinosa*. B: An ogre-faced spider hanging upside-down with its net. Used from [1].

Spiders lack anything resembling vertebrate ears. Instead, they “hear” (detect air vibrations) with long skinny leg hairs called trichobothria and exoskeletal slits called slit sensilla. Other spiders use vibrations for sensing wind for placing webs or finding struggling prey in their webs [3]. But the vibration sensing, processing, and response in Deinopis spinosa is tuned to a 250-1000 Hz range, perfect for detecting flying insects [2]. This is no coincidence: flying insects are betrayed by the very motion that once helped them thrive—the flapping of their wings. The hunter pinpoints its prey from these vibrations and lashes out in a backwards strike. Thanks to a specialized spinning plate and leg comb called the cribellum and calamistrum respectively, the Deinopid silk is stickier than most. Our protagonist (or antagonist?) just needs to graze its victim and dinner is served.

Come morning, the ogre-faced net-casting spider packs up its spidey bags of tricks and treats and returns to a low-lying existence. Its large simple eyes, the largest of any arthropod and 2000 times more light-sensitive than ours, are so sensitive that they risk damage from direct sunlight [4, 5]. Deinopis solves this issue by breaking down a membrane in the photoreceptors each dawn, storing the parts, and rebuilding said membrane come dusk. It sounds like a lot of extra work, but for these successful hunters it is apparently worth it. Plus, their gigantic eyes make them far cuter than any ogre I have ever seen!

Since I’m willing to bet that you, dear reader, are not an insect, I encourage you to put aside any terror and appreciate for a moment how incredible these adaptations are. And the ogre-faced net-casting spider is only one of the thousands of unique spiders with complex strategies that have evolved to fill nearly every niche imaginable. Opening your mind to what we often dismiss as “creepy crawlies” might just turn your fear into fascination as it has for me and many others.

Works Cited

[1] Stafstrom, J. A., Menda, G., Nitzany, E. I., Hebets, E. A., & Hoy, R. R. (2020). Ogre-Faced, Net-Casting Spiders Use Auditory Cues to Detect Airborne Prey. Current Biology, 30(24), 5033-5039.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.048

[2] Stafstrom, J. A., & Hebets, E. A. (2016). Nocturnal foraging enhanced by enlarged secondary eyes in a net-casting spider. Biology Letters, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0152

[3] Foelix, R. F. (2011). Biology of spiders (3rd ed). Oxford University Press. Google Books link

[4] Blest, A. D., & Land, M. F. (1977). The physiological optics of Dinopis subrufus L. Koch: A fish-lens in a spider. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 196(1123), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1977.0037

[5] Blest, A. D. (1978). The rapid synthesis and destruction of photoreceptor membrane by a dinopid spider: A daily cycle. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 200(1141). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1978.0027